Manuscript for Proceeding of The 5th International workshop on complex systems.(IWCS2007)

Network Motif of Water

Masakazu Matsumoto, Akinori Baba*, and Iwao Ohmine

Research Center for Materials Science and Chemistry Department, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa, Nagoya, 464-8602 JAPAN, and

Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Faculty of Science, Kobe University, Rokkodai, Nada, Kobe, 657-8501 JAPAN

Abstract

The network motif of water, vitrite, is introduced to elucidate the intermediate-range order in supercooled liquid water. Unstrained vitrites aggregate in supercooled liquid water to form very stable domain. Hydrogen bond rearrangements mostly occur outside the domain, so that the dynamical heterogeneity also stands out. Pre-peak in the structure factor of low density amorphous ice is reproduced by inter-vitrite structure factor. The vitrite can therefore be regarded as a plausible building block of the intermediate-range order and heterogeneity in supercooled liquid water and low-density amorphous ice.

Keywords: Amorphous water; Low-density water; Network motif; Water structure.

PACS: 61.43.Bn, 64.70.Ja, 64.60.aq, 61.20.Gy DOI:10.1063/1.2897788

INTRODUCTION

The past ten years of research in supercooled liquid have produced major theoretical and experimental advancements. Anomalies of liquid water such as expansion below 4 degree C, for example, are now considered to arise from the properties of metastable forms of water. 1 The expansion accelerates below the melting point, and it is hypothecated to become the low-density amorphous ice if crystal nucleation does not intercept. This expanding “low-density liquid water” has structural similarities with the low-density amorphous ice (LDA). 2

Recent study revealed that any liquid that expands as it cools must have two distinct phases. 3 Mishima reported that there are actually two different amorphous ice phases, low- and high-density amorphous ices (LDA and HDA), and observed the first-order phase transition between them. 4 Two amorphous ices even share the interface when they coexist. 5 That is, the two “phases” have distinct structural difference, though both are random phases. In this case, LDA is more ordered phase than HDA.

Then, what kind of order emerges in LDA? What is the origin of the expansion in supercooled liquid water? Does the heterogeneity in liquid water really come from hypothetical liquid-liquid coexistence? To answer these questions, first of all, we must understand the microscopic structure of LDA and its difference from HDA. Structure of LDA is characterized by the tetrahedral local order and the intermediate-range order in the hydrogen bond network (HBN). Such a structure, also known as continuous random network (CRN), has been studied for a long time as the model of tetrahedral semiconductors, and its short-range order was assessed in terms of Voronoi polyhedra, coordination number, rings, etc. The existence of intermediate-range order was also assessed in terms of low configurational entropy, a distinct pre-peak in the structure factor, etc. 6,7: nevertheless, its structure is still not identified. 8

We characterize the network topology of supercooled liquid water by introducing the network motif (NM) called “vitrite”. The vitrite is not a random rubble of the network but a non-overlapping tile of the mosaic, i.e. vitrites are found to aggregate each other to fill large part of LDA. 9 We also try to explain the intermediate-range order observed by diffraction experiments in terms of spatial correlation between vitrites.

METHOD

Determination of Network Motif

Water is a network-forming substance. HBN of liquid water is fully percolated 3-dimensionally. We here use terms “edge” and “vertex” when only the network topology is considered, while “bond” and “node” for the real structure embedded in 3-dimensional space. In terms of complex network, the order (i.e. number of edges at a vertex) of HBN is about 4 on average, so that the network is not scale-free. Bond length of HBN is almost fixed, so HBN topology is not a small world network. Nevertheless, HBN has own characteristics in both geometry and topology.

There are more than ten different crystal ice phases, extraordinarily large variety for small molecule like water. Surprisingly, water molecules have four hydrogen bonds (HB) and Pauling’s ice rule is satisfied in all the ice phases even under super-high pressure. 10 Thus the ice phases are identified not by local coordination number but by the difference in the HBN topology. As for the network geometry, water molecule prefers tetrahedral local order (TLO). Constraints in both geometry and topology yield the cage-like structure that is common motif of HBN of water. For example, HBN of the hexagonal ice is built of cage-like 12-mer. (Fig. 1(a)) Cubic ice Ic is built of network motifs with 10 water molecules. (Fig. 1(b)) Clathrate hydrates are also built of polyhedral cages with 20-30 water molecules. (Fig. 1(c)) Such cage-like structures are also found in the liquid water, especially at supercooled state. 11 Cage-like structure contains a void, and that the increase of such structures is considered to be the origin of expansion when liquid water is cooled. 12

](storage:[Network Motif of Water](/Network Motif of Water)/F1_0.jpeg)

FIGURE 1. Cage-like structure of (a) hexagonal ice, (b) cubic ice, and (c) clathrate hydrate are illustrated. A ball and stick correspond to a water molecule and a hydrogen bond, respectively.

Any kind of given subgraph in HBN of water can be searched by means of some graph-matching algorithms. Thus we can enumerate the population of ice motifs in liquid water. When a set of unit structures are given, one can even build up the possible crystal structures combinatorially, that has been done for the family of zeolites. Some of them are isomorphic with ice network. 13

Such a strategy is, however, not always helpful to understand the total topology of the random network of supercooled liquid water. While ice motif is not popular in liquid water, there are too ample kinds of motifs possible for matching templates. Although the precedent works also demonstrated the locally preferred structures (e.g. vitron, amorphon, etc.), it seems unreasonable to choose the limited set of local structures as the representative of glassy material. Instead, some systematic method to tessellate the network and to enumerate NM is wanted.

We introduce “vitrites”, a family of network motifs satisfying the common topological conditions. A vitrite is defined as a NM built of surface rings encapsulating a void. It must satisfy the following conditions;

- each edge is shared by two rings,

- each vertex is shared by 2 or 3 rings, and

- the graph obeys the Euler’s formula, F-E+V=2, where F, E, and V are number of rings, edges, and vertices, respectively. First condition certifies the closed surface. Second condition comes from the characteristics of the network with TLO. It is purely a topological definition but still guarantee the hollow geometry by the third condition. See Ref. 9 for more detail on the definition of the vitrites. Major vitrites in water at low temperature are illustrated in Fig. 2.

](storage:[Network Motif of Water](/Network Motif of Water)/F2_0.jpeg)

FIGURE 2. Six typical vitrites in liquid water are illustrated. A ball and a stick correspond to a water molecule and a hydrogen bond, respectively. All vitrites found in HBN are available online at the vitrite database: http://vitrite.chem.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Molecular dynamics simulations are performed to obtain the equilibrium water configurations in the temperature range between 200K and 360K under zero and 3,000 atm. Simulation details are described in the previous paper. 9 In the present work, Nada’s 6-site water model is used. 14 All the results are reconfirmed by the calculations with TIP4P/2005 water model. 15 The topological properties of the HBN are analyzed in terms of the inherent structures to eliminate the ambiguity over the hydrogen bond criteria.

RESULTS

Distribution of Network Motifs

Topological differences among normal liquid water, water at low temperature and water under high pressure are elucidated by their NM statistics.

In supercooled liquid water, each node (water molecules) prefers to be in regular-tetrahedral local coordination. This preference restricts the variety of intermediate-range network topology. Water at low temperature thus has almost defect-free network consisting mainly of 5- to 7-membered rings, and is filled with stable vitrites with small distortion. (Fig. 3) Hydrogen bonds belonging to unstrained vitrites actually have much longer lifetime than the average.9 Although NM of ice is also stable, it is not quite popular in supercooled liquid water because of its high symmetry number.

At higher temperature and under high pressure of 3,000 atm, number of the vitrites decreases; they cover only a half of the HB network, and the other half consists of entangled topologies where vitrite-like compact NM is absent.9

](storage:[Network Motif of Water](/Network Motif of Water)/0990_0.png)

FIGURE 3. (Color Online) All the vitrites found in the hydrogen bond network in a snapshot at 200K is illustrated, where water molecules and hydrogen bonds are not drawn and the vitrites are depicted by translucent hulls. Vitrites of the same color are identical topologically. A small gap is put between vitrites in order to show the internal structure. The network is totally tessellated into vitrites.

Vitrite Aggregation

In supercooled liquid water, vitrites consist of 5- to 7-membered rings predominate because their surface rings can reduce strains (angular distortion) when they are in the appropriate conformations (boat, chair, and so on). Such vitrites aggregate by sharing the surface rings of the same conformation to form very stable network with TLO.9 Inside the aggregate, a casual network rearrangement at a bond affects the topology of all the vitrites sharing the bond and might result in increase of strain. Hence, network rearrangement would be as difficult as that inside crystal ice. Actually, most rearrangements take place at the surface of the aggregate but not in the aggregate. (Fig. 4) Thus the vitrite aggregation emerges heterogeneity of both HBN structure and rearrangement in supercooled water, i.e., “ice-like” domain is topologically identified by the aggregation of vitrites. Note that hydrogen bonds in vitrite aggregates also have longer lifetime.9

](storage:[Network Motif of Water](/Network Motif of Water)/F4_0.jpeg)

FIGURE 4. Positions of the surface rings of the vitrite aggregates, hydrogen bond rearrangements, and network “defects” during 10 ps, are drawn with translucent flakes, lines, and black dots, respectively. Temperature is 230K and pressure is 0 atm. Water molecules are omitted. All 10 snapshots during 10 ps are overlaid in the picture, so the dark area of flakes corresponds the high probability of finding a surface ring. Top-right region, where no flakes, lines, nor dots are drawn, indicates that the space is filled by the vitrite aggregates without “defects” and no HB rearrangements happen there. Note that the heterogeneity in this picture lasts far longer than 1 ns.

First Sharp Diffraction Peak

The concept of vitrites is also useful to interpret the “First Sharp Diffraction Peak (FSDP)” observed in the x-ray structure factor (SF) of LDA ice. 16 FSDP is found to exist in all network-forming ionic liquids, like ZnCl2 and SiO2. 17 This peak is not attributed to any real-space partial pair distribution functions. 18 Instead, it is considered to correspond to the correlation length among cavities, which exist in an amorphous network. Barker and co-workers applied the Voronoi analysis on LDL and HDL water and defined the position of voids at vertices of Voronoi polyhedra. They have found that the peak of the void-void SF corresponds quite closely to FSDP. 18 It must be noted, however, that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a void and a physical “cavity” in the network structure.

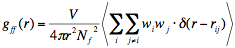

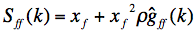

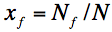

The origin of the void-void correlation, i.e. of FSDP, is well explained in terms of the spatial correlation among the vitrites. A vitrite has an “empty volume”, a cavity, in it. By assigning the virtual atoms at the centers of vitrites and their weighting factors proportional to the vitrite’s “volumes” (i.e. effective number of molecules constructing the vitrite. See Ref. 9.) on the corresponding virtual atoms, then we can calculate the inter-vitrite pair correlation function (that is, the pair correlation function of these volume-weighted virtual atoms) as

(1)

where w!!i!! is the “volume” of ith vitrite and

. The inter-vitrite SF is defined by the Fourier transform of this inter-vitrite pair correlation function g!!ff!!(r), such as:

(2)

where x!!f!! is coverage by vitrites, i.e.

.

The inter-vitrite SF thus obtained, shown in Figure 5, has a distinguished single peak at around 1.6&197;-1. 18 FSDP of the inter-vitrite SF becomes very small for higher temperature. FSDP of oxygen-oxygen SF of water yields the same behavior. When the volume-weighted virtual atoms are placed at the center of the vitrites, FSDP, which is apparent in oxygen-oxygen SF, vanishes in the total (i.e. oxygen + virtual atoms) SF (Figure 5), 19 showing that this peak indeed arises from the distribution of vitrites.

](storage:[Network Motif of Water](/Network Motif of Water)/F5_0.jpeg)

FIGURE 5. SFs from experiments and those obtained from the simulations. (a) X-ray SF of LDA ice of D2O at 77K taken from Ref. 16. (b) SF between Oxygen atoms. (c) SF between virtual atoms. (d) SF of both Oxygen and virtual atoms. Solid, dashed, and dotted lines correspond to 230K, 260K, and 290K, respectively, and pressure is zero. Instantaneous structures (instead of inherent structures used in other graphs) are used in order to compare with experimental data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is partially supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on “Meso-timescale dynamics of crystallization” (Grant No. 14,077,210), “Chemistry on Homogeneous Nucleation” (Grant No. 15,685,002), and “Water Dynamics” (Grant No. 1,400,100) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. Calculations were carried out partly by using the supercomputers at Nagoya University Information Technology Center and at Research Center for Computational Science of Okazaki National Institute.

REFERENCES

- O. Mishima and H. E. Stanley, Nature 396, 329-335 (1998).

- M.-C. Bellissent-Funel, J. Teixeira, and L. Bosio, J. Chem. Phys. 87, 2231-2235 (1987).

- F. Sciortino, E. La Nave, and P. Tartaglia, Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 155701 (2003).

- O.Mishima, J. Chem. Phys. 100, 5910-5912 (1994).

- O. Mishima and Y. Suzuki, Nature 419, 599-603 (2002).

- E. Whalley, D. D. Klug, and Y. P. Handa, Nature 342, 782-783 (1989).

- D. R. Barker, M. Wilson, and P. A. Madden, Phys. Rev. E 62, 1427-1430 (2000).

- J. R. Errington et al, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 215503 (2002).

- M. Matsumoto, A. Baba, and I. Ohmine, J. Chem. Phys., 127, 134504 (2007).

- D. Eisenberg and W. Kauzmann, The structure and properties of water, Oxford Univ. Press, London, 1969, pp.79-92.

- F.H.Stillinger, Science 209, 451-457 (1980).

- P. G. Debenedetti, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15, R1669-R1726 (2003).

- O. D. Friedrichs, A. W. M. Dress, Nature (London) 400, 644-647 (1999).

- H. Nada and J.-P J.M. van der Eerden, J. Chem. Phys. 103, 7401-7413 (2003).

- J. L. F. Abascal and C. Vega, J. Chem. Phys. 123, 234505 (2005).

- A. Bizid, L. Bosio, A. Defrain, and M. Oumezzine, J. Chem. Phys. 87, 2225-2230 (1987).

- P. S. Salmon, Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 437, 591-606 (1992); 445, 351-365 (1994).

- D. R. Barker, M. Wilson, and P. A. Madden, Phys. Rev. E 62, 1427-1430 (2000).

- M. Popescu, Journal of Optoelectronics and Advanced Materials 5, 1059-1068 (2003).